Ohne Titel (Landschaft Bolivien) IV (untitled (landscape bolivia IV), 1999, oil, acryl and lack on canvas, 115 x 135 cm

Ohne Titel (Landschaft Bolivien) V (untitled (landscape bolivia V), 1999, oil, acryl and lack on canvas, 140 x 150 cm

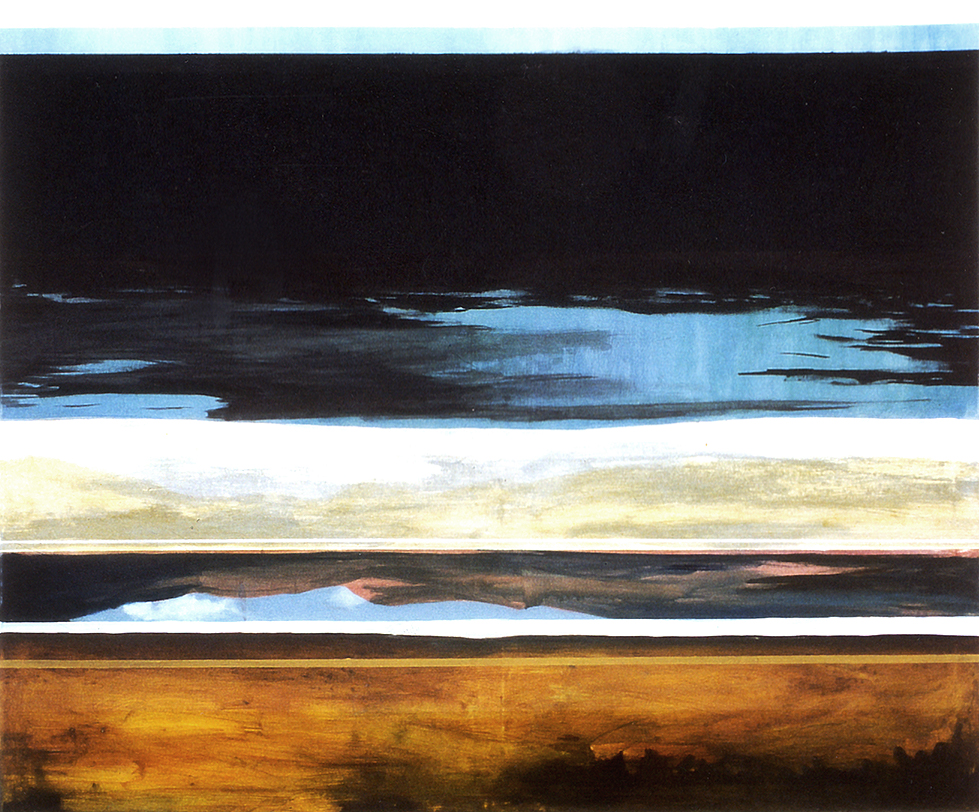

Ohne Titel (Landschaft Bolivien) I (untitled (landscape bolivia I), 1999, oil, acryl and lack on canvas, je 120 x 140 cm

Ohne Titel (Landschaft Bolivien) II (untitled (landscape bolivia I), 1999, oil, acryl and lack on canvas, je 120 x 140 cm

Ohne Titel (Landschaft Bolivien) III (untitled (landscape bolivia I), 1999, oil, acryl and lack on canvas, je 120 x 140 cm |

The Bolivian plateauMan lives and dies in what he sees. But he only sees what he thinks. (Paul Claudel)

Represented is the experience of observing an impossibility-it is

impossible to see what one cannot imagine: endlessness, and it's also

impossible to integrate oneself into this landscape that exists

independent from the gaze of the viewer. Impossible, as the paintings

ultimately also suggest, is the calm, ordered gaze of the observer of

this landscape at all. Consistently represented in the paintings is a

moment of motion, that suggest that the viewer is a traveler, who above

all constructs his image of the landscape in his mind, without being

able to actually grasp the landscape. While traveling, a space devoid of

people passes by, that offers him no point of reference. The

recognition of the landscape in one's consciousness, is ultimately only

in and through movement possible: the observer then abandons the notion

of ordering the things around himself from a fixed location. But in and

through the consciousness another thing happens: the grinding facticity

of things is in movement again annulled. Space is relative-and with it

the organizing gaze.

|